Tampa’s Historic Desegregation Protests

Throughout much of Tampa’s early history, we had a large slave population. It was Florida’s largest industry, with about 44% of the population of Florida being enslaved Africans. That was until the emancipation proclamation was put into action by Abraham Lincoln, freeing all slaves across the country from their masters. This wasn’t the end all for equal treatment, however. Black people continued to be treated as lesser than by governments and society for many decades afterward. Eventually, this settled itself in the mid-1900s, a time of Jim Crow laws and segregation, where people were treated “separately but equally” meaning that almost everything from bathrooms, to water fountains, to parks was segregated. Among the many separations between white and black people this brought, one of the biggest was the separation of schools, clearly differentiating “white” and “black” schools.

White and black schools were primarily different by race of the student population, but most noticeably, black schools were in poorer areas with less funding. Because of this, white schools almost always came with better education rates, test scores, and faculty pay. This continued for many years until the civil rights movement finally came to fruition in 1969 when Tampa had begun its period of desegregation. This brought about a myriad of social changes, many of which were very positive. However, there were a few drawbacks to this act, namely in forced schooling.

One of the biggest aspects of change for daily life in Tampa was the promise that schools would be made free for all to attend, rather than separated by race. While most people thought that this change would be brought about by giving students free choice in schooling, the government instead forced black students out of their schools and into white schools. Here in downtown Tampa, Blake took the brunt of this, with many students being transferred from Blake to Plant City HS prematurely because of location.

“We had no idea it was coming, we thought we were gonna graduate from a black school and ended up graduating from an integrated school”, said County Commissioner Gwen Meyers, a Blake alumni who was transferred to Plant City in 1970.

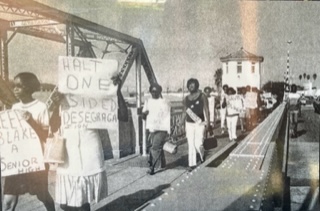

Initially, everyone was surprised at this, shocked that they were forced to go to a school they didn’t choose. This started a widespread backlash which turned into large protests. Many black students protested this decision for a few reasons:

First, many students were sent to zones far out of their living area, increasing their commute time and making it harder for them to get to school. As mentioned before, black schools were in poorer areas with large black populations, while white schools were much farther out in richer areas. These were also generally in suburban areas that expected usage of a car, which not everyone being transferred had access to.

Second, the people at the transfer schools were not welcoming of the people coming in. Curtis A. Wright, another Blake alumni who graduated in 1969 said “My sister only lasted one day at a white school, a kid was being aggressive and she jumped up and fought him, so she got kicked out.” Teachers and students were showing aggression towards the new students coming in, calling them slurs, and getting violent on occasion which led to black students getting angrier and angrier with this placement.

Third, they felt that this act was the opposite of what desegregation should be. Black students felt that by making them go to a certain school, they were taking away the right to choose their schooling. As well, they felt that it was unfair to force the black kids to go to white schools, and never vice versa. The argument was that the government, in a racist move, was sending black students to white schools because white students were too good for black schools.

All of this anger culminated in several protests over many years. Commissioner Meyers says that, “The protests were to raise awareness, to show that we saw what happened and we cared.” Almost all of the protests were marches outside of white schools by black students. One very important point the protestors made was to maintain peace, but this wasn’t always possible. Some of these protests turned into riots by the anger from injustice, according to Curtis Wright “a kid from Blake High School was shot, and I’m very familiar with the riots that came afterward.” Nevertheless, the protests were widespread in Tampa and had a strong message to back them.

Unfortunately, even with all the efforts of the students, it took several years for this message to take effect. Black students didn’t regain the ability to choose their schools until the 1980s, and schools wouldn’t become fully desegregated until the 1990s. Despite that, the students of Blake and Tampa in general eventually had their message come to absolute fruition, causing an age of significant diversity throughout the 21st century in the magnet program.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Blake High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.